Theory of Mind in Autism: Why Kids Might Seem "Unempathetic"

Theory of mind in autism affects how kids understand others' thoughts and feelings—learn why they may appear unempathetic and how to better support them.

Theory of Mind in Autism: Why Kids Might Seem "Unempathetic"

Key Points:

- Children with autism may appear unempathetic due to challenges with theory of mind—the ability to understand others' perspectives and emotions.

- Delays in developing theory of mind can impact social interactions, friendships, and communication.

- ABA therapy can support children in building perspective-taking and emotional understanding skills.

Empathy is something most parents expect to see naturally unfold as their child grows. But when a child with autism seems detached, uninterested, or unaware of how others feel, it can be both confusing and painful for families. The issue isn’t a lack of love—it’s often a lag in something called theory of mind.

Theory of mind in autism refers to the difficulty some children have in recognizing that others have thoughts, feelings, and beliefs different from their own. This isn’t about being cold or uncaring. It’s about developmental timing and the way the autistic brain processes social information. And understanding this concept can shift the way we support and connect with autistic children in meaningful ways.

What is Theory of Mind?

Theory of mind is the ability to understand that other people have their own thoughts, desires, and perspectives. It’s what helps a child know that Mommy is sad even if Mommy doesn’t say so out loud. It’s what helps kids play pretend, resolve conflicts, and take turns in conversation.

For many children, theory of mind begins developing around age 3 and becomes more refined by ages 5–6. But for children with autism, this development often follows a different trajectory.

Researchers have found that many autistic children struggle with classic theory of mind tasks—like predicting what someone else will do when they don’t have all the information the child has. This creates roadblocks in social situations, not because the child is rude or indifferent, but because their brain processes the social world differently.

Why Autistic Children Might Seem "Unempathetic"

If you’ve ever watched your child ignore a friend’s tears or laugh at an inappropriate time, it’s tempting to assume they lack empathy. But here’s the truth: most children with autism do care. They just might not show it the way you expect.

Here’s why that disconnect can happen:

1. Difficulty Reading Nonverbal Cues

Most people rely heavily on facial expressions, tone of voice, and body language to communicate feelings. But for many autistic children, these signals don’t register automatically. So while another child might recognize a frown as a sign of sadness, an autistic child might miss that cue completely.

2. Struggles with Perspective-Taking

Without theory of mind, it’s hard to realize that someone else sees a situation differently. For example, if a child knows where a toy is hidden, they might assume everyone else knows too. This makes sharing, helping, or apologizing trickier—they’re not being stubborn, they truly don’t see the mismatch in understanding.

3. Delayed Emotional Understanding

Even if a child can tell that someone is sad, they may not understand why or what response is appropriate. This is often interpreted as coldness when, in reality, the child just hasn’t yet developed that skill.

4. Processing Overload

In emotionally charged moments, some autistic children become overwhelmed. They may shut down or respond in ways that look dismissive—like walking away or changing the subject—when they’re actually trying to manage their own stress.

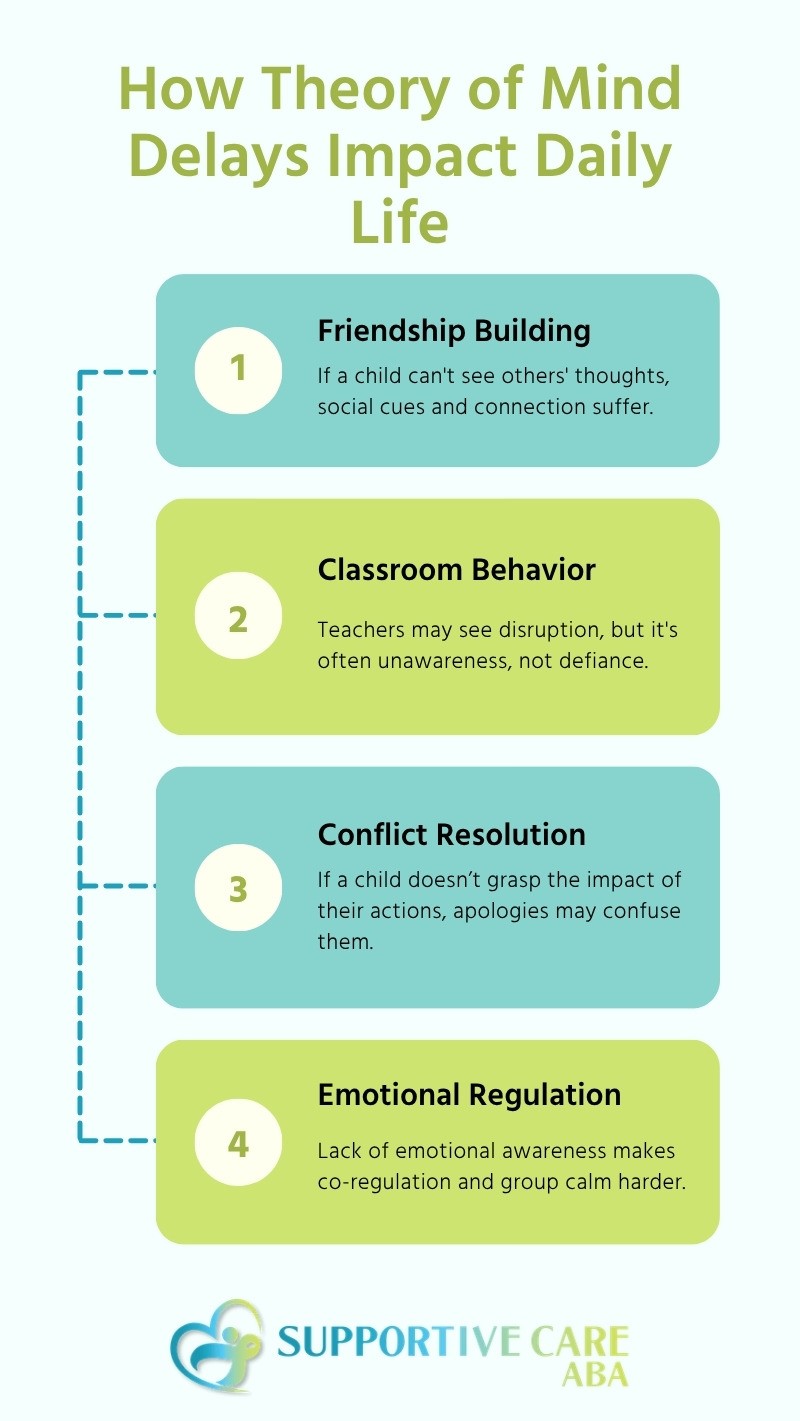

How Theory of Mind Delays Impact Daily Life

When a child struggles with theory of mind, it shows up in more than just playdates. It can shape how they interact at school, in therapy, and at home.

Let’s look at a few common areas where these challenges come into play:

These aren’t fixed traits—they’re developmental delays that can be addressed with the right strategies and support. That’s where Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy can play a critical role.

5 Signs Your Child May Be Struggling with Theory of Mind

While every child is different, there are a few indicators that might suggest a challenge with theory of mind. These aren’t meant to diagnose but to help parents reflect and observe.

Here are some signs to watch for:

- Difficulty Understanding Jokes or Sarcasm: They may take everything literally, missing the hidden meanings that are common in everyday speech.

- Problems with Pretend Play: They might show little interest in make-believe games or struggle to understand role-play scenarios.

- Trouble Explaining Others’ Behavior: If you ask, “Why do you think your friend was upset?” your child might genuinely not know or offer a response focused only on their own point of view.

- Limited Sharing of Interests: Children with theory of mind delays might talk about their interests without checking if others are interested or engaged.

- Misreading Social Situations: They might laugh at someone getting hurt or ignore someone asking for help—not out of malice, but from a missed social cue.

Recognizing these patterns early allows for targeted interventions, many of which can be addressed in ABA sessions tailored to social and emotional development.

Supporting Theory of Mind Through Everyday Routines

Parents play a key role in helping their children build perspective-taking skills. These strategies can be embedded into daily life and don’t require formal training—just intentionality and patience.

Here’s how to start:

1. Use "Think Alouds"

Narrate your thoughts during problem-solving moments. For example: “Hmm, if I take the last cookie, your sister might feel sad because she didn’t get one. Maybe I should offer to split it.”

This helps your child see the connection between thoughts, feelings, and actions.

2. Ask Open-Ended Questions

Instead of “Was that nice?”, ask, “How do you think your friend felt when that happened?” It nudges your child to think beyond their own perspective.

3. Practice Social Stories

These are short, personalized stories that walk through social situations. They help a child understand others’ points of view and predict reactions.

4. Label Emotions Regularly

Use everyday moments to say things like, “He looks frustrated. See his face?” Pairing facial cues with feeling words builds emotional literacy.

5. Play Perspective-Taking Games

Guessing games, role plays, and board games that require turn-taking all build foundational theory of mind skills.

These tools don’t always create instant change, but with consistency and reinforcement—especially when paired with ABA strategies—they can make a meaningful difference over time.

How ABA Therapy Can Help Develop Theory of Mind

Supportive Care ABA works with families to help children with autism develop the building blocks of social understanding, including theory of mind. Through structured, individualized programs, behavior technicians and BCBAs (Board Certified Behavior Analysts) teach skills like:

- Recognizing emotions in others

- Predicting reactions based on social context

- Taking turns in conversation

- Responding appropriately to others’ feelings

ABA doesn’t force social behaviors—it breaks them down into teachable steps that a child can master in a safe, encouraging environment. For example, rather than telling a child “be empathetic,” ABA therapists model what that looks like, reinforce small wins, and gradually build complexity.

Over time, many children become more aware of how their actions affect others, gain confidence in social settings, and reduce the kinds of misunderstandings that once led to isolation or frustration.

Final Thoughts: Empathy Looks Different, But It’s There

If your child seems “unempathetic,” it’s not a character flaw. It’s often a reflection of how they process the world—and with the right support, those gaps can close. Theory of mind in autism is a challenge, but it’s one we understand and know how to work with.

Whether your child is struggling to connect with peers, understand feelings, or respond to social cues, Supportive Care ABA is here to help. We provide individualized ABA therapy in Oklahoma, Georgia, Virginia, Indiana, and North Carolina, focusing on skills that build not just communication, but real connection.

Let’s help your child develop the tools they need to relate, respond, and thrive. Contact us to learn how we can support your family.

%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)